I am a direct descendent, on my father’s side, of the Hodgins, Memery and Gray families.

In 1819, a small number of Fishermen from Brixham, Devon came over to Ireland at the invitation of the then Harbour Master James Stewart, who was attempting to invigorate the fishing industry in Ringsend, Dublin. The Brixham boats, crews and fishing techniques were, at this time, state of the art, the Brixham smack being considered the best fishing smack in the British Isles.

The Brixham trawlers had been venturing into Irish fishing grounds in Dublin Bay in the early years of the century. The potential opportunity to develop the industry was not lost on the Dublin Harbour Master, despite concerns about their trawl techniques and damage to fish and the sea bed. The high quality craft and beam-trawling techniques permitted deep sea fishing and were soon adopted by the local fishermen, giving a substantial boost to the local economy. At least twelve Devon families subsequently migrated over the next 30 years, settling in Ringsend and Dun Laoire. Names that appear to be associated with the migration include; Burnham, Pile, Rowden, Bartlett, Symes, Memery, Snell, Blackmore, Voisey, Bond, Pullen, Elliot and Gray. They were known locally as the Torbays, indicating their origins from Brixham, Torquay, Newtown Abbot and Dittisham, towns circling Tor Bay in South Devon. A detailed account of this migration can be found in Edmond Symes’s paper ‘The Torbay Fishermen in Ringsend’. Of the migrating families, the Memerys and the possibly the Grays are my ancestors.

A post on ‘Dundrummethodist’ (author unknown) describes the migration as follows

‘...that a fleet of over 80 Torbay fishing boats carrying wives and families, set sail for Ringsend in the late 1820’s with the intention of settling there. They came in on a wave of immigration, each boat carrying a copy of the Holy Bible that was given as a personal gift from Reverend Lyte. Their surnames included Alexander, Andrews, Aplin, Barr, Beckett, Blackmore, Boon, Bowden, Davy,

Dunwoody, Elliot, Gray, Hawkins, Hodgins, Jones, Leech, Lewis, Ince, Marshall, Mays, Memery, Payne, Pullen, Rackley, Richardson, Rowden, Saunders, Simms,

Sims, Syms, Weldrick and Weir’.

(NB this list in more extensive than Symes’s list. My own research shows Hodgins’s came from Lisburn for example)

This picture was painted by Alexander Williams and is described by Cormac Louth as follows ;

The trawlers, or smacks as they were known, were large, single-masted, gaff rigged vessels that fished with beam trawls. The smacks moored in the area that is today taken up with moorings for the Poolbeg Yacht Club. This part of the Port was traditionally known as the ‘Trawlers Pond’. In 1911, Alexander Williams illustrated a series of books for Stephen Gwynne entitled Beautiful Ireland. In the book dealing with Leinster, there is a splendid illustration of shipping in Dublin Port showing some of the Ringsend trawlers with their distinctive reddish brown sails and the trawl beams along one side.

The following accounts (from Irish newspaper archive) refer to the Torbays. The name Blackmore was one that we were familiar with growing up. Cliff Gempton a Brixham resident of today that I have been in touch with is descended from Sarah Blackmore (GGG grandmmother). Her three brothers migrated from Brixham; Samuel, Alexander and George.

Ringsend had always been associated with sea faring and related activities, being the first landing point for Dublin in earlier times, and the point at which revenue was collected for ships travelling further into Dublin. In fact the steeple of St Matthews Church in Irishtown (where I was christened) was added in c. 1780 to act as a navigation mark for ships. Ringsend had already established itself as an industrial community. The fishing trade in Ringsend, prior to the migration was a central plank in the local economy, with support industries and activities such as boat building, sail and rope making and bottle works. Its nickname ‘Raytown’ comes from the popularity of fishing and eating ray fish. A report from the Freemans Journal in 1835 below suggests the Torbays effectively boosted a flagging industry. Perhaps not welcoming the migrants at first, the Ringsend seafarers inevitable integrated with the Brixham Torbays, and they too became excellent trawlermen.

Comerford describes Thorncastle street in Ringsend in 1845 as follows;

In 1845, during the great famine, the residents of Ringsend were not as badly affected as other places in Ireland. They lived on fish and Indian corn given by Sidney Herbert, the 14th Earl of Pembroke, known to have been one of the decent Irish landlords during the famine. In 1856 there were 2,064 inhabitants and 190 houses in Ringsend. There were 34 entries for Thorncastle Street, predominantly shipbuilders, vintners and provision dealers. Other interesting entries were pilots, a coal merchant and a blacksmith.

This way of life came to an end, as sail power was eventually replaced by steam. Trawling/seafaring was a hard and dangerous occupation, depending chiefly on manual skills; handling and hauling nets, gutting and salting fish on deck and in all weathers. While the families of trawlermen may have eaten better than labourers in the inland counties during the famine, they relied on catch that could never be predicted and might never make it back to land in the event of extreme seas and winds. An account in the Freeman’s Journal of a storm in 1894 (see below) gives a sense of the fear Ringsend families frequently lived in. A boat lost was a major blow to a family, a crew lost even more so. The practice of crewing with sons meant several members of one family could be lost at sea in one incident. Those who could own boats may have adopted the practice of not crewing their own boats, to mitigate against the possibility of their family losing both boat and crew in the event of a storm.

Evidence that the Torbays were in Ringsend comes from memorials in St Matthews parish in 1840, and an account reported by historian Turtle Bunbury, assuming errors only in spelling;

Here lieth the remains of Jane BARTLETT, a native of Brixham, Devonshire.

She died in Sandymount, 10th Sept. 1848, aged 55 years. Also Harriet,

daughter of the above, died 20th April, 1853, age 21 years. Also Thomas

BARTLETT, of Newgrove house, Sandymount, Master Mariner, husband and

father of the above, died 13th May, 1859, age 65 years.

One dark evening in October 1829, Samuel Bartlet, one of the Ringsend ‘Tar-bays’, was out fishing in Dublin Bay when three large boats abruptly hove into view and came alongside him. Upwards of forty men then swung onto Bartlet’s boat. The pirates knocked Bartlet down with a paddle and threatened to throw him overboard. Somehow Bartlet managed to escape but the ‘ruffians’ successfully plundered his vessel of all fish, before cutting up his nets, destroying his gear and hurling everything into the sea.

Bunbury also reports that the Rev Lyte, from Brixham was a frequent visitor to Ringsend. He wrote the hymn ‘Abide with me’, a favourite of our Grandmother. According to the ‘Dundrummethodist’

‘Lyte wrote 234 hymns (including “Abide with Me”) which became widely used in Britain and America. He also developed a large Sunday school in the Torbay area. While working against the slave trade with Wilberforce, Lyte also

worked to improve the standard of education in the U.K. Not surprisingly, Lyte became a friend to the Torbay fishermen and their families.According to Ringsend tradition, it was because of Lyte’s description of the wealth of Dublin Bay fishing, ….’ the migration occured

(This contrasts with Symes’ account which attributed the migration to the work of the Dublin Harbour master)

St Matthews was built in 1703, although the original steeple was blown down in a hurricane in 1839. A school for boys was added in 1832, and it could be presumed that the Torbays were instrumental in this, as they are likley to have swelled the ranks of the local Protestant community. The sexton of the Schoolhouse c. 1860 was a William Creese, a Brixham name, and very likley to be related to our Great Great Grandmother, as outlined later. A school for girls was built in 1904.

I have searched the graveyard at St Matthews but cannot find any headstones with either Hodgins, Gray or Memery. However many are completely unreadable. It is also possible that our ancestors could not afford headstones. Ringsend at the time of the migration, although a thriving fishing community, was not necessarily a pleasant place to live;

Lewis in his Topographical Dictionary of Dublin 1837 described Ringsend as having a mean and dilapidated appearance, having fallen into decay since discontinuance of its extensive salt-works’.

By 1851 Ringsend has a population of 2,064, and although a good proportion of the population was also engaged in the fishing industry it was starting to loose its prime importance as a maritime centre. Ringsend had extensive glass and salt works. In addition there was ship and boat building to a small extent, an iron foundry producing iron boats, steam engines and boilers, and a Sal-Ammonia factory. There was an ‘omnibus service to and from College Green at a fare of two pence’.

Although famine may not have posed the same threat to these seafaring families as those in rural Ireland, this did not mean they were protected from poverty, which was rife in Dublin at this time. Ringsend was no exception to the general poverty experienced in the late 19th century and early 20th century. According to the National Archives, in 1911, at least one third of Dublin families lived in one room accommodation. Industry made the town unpleasant and despite activity, substantial prosperity was curtailed with the movement of the steam packet service to Kingstown and Howth. Ringsend was not favoured by the emerging middle class as a place to live, due to its industrial environment. The wealthier, preferring Sandymount and Donnybrook, left Ringsend to its working class origins, which despite the associated poverty, was said to be borne proudly by Ringsenders.

By 1848, when the Torbay migration was near completion, Ringsend had about 150 houses; “…with a population of 1,755. It consisted of several streets of very indifferent and irregularly built houses, chiefly poor and mainly dilapidated. Amongst the few streets the names “Quality Row” and “Whiskey Row”, indicate the class distinctions and the commercial activities of the period. Thorncastle Street, an address that crops up in many searches for the Memery, Gray and Hodgins families consisted of small industrial premises and tenements. In 1876, 18 buildings on the street were tenements. In 1905, a labour project to alleviate dire need was recorded, to provide 9 hours work a day, tenpence and a meal.

The image below shows Thorncastle Street c. 1900 while the map shows Ringsend today. The street names that come up in the searches for Memery, Hodgins and Gray families are all there; Thorncastle street, Cambridge Road, York Road, Pembroke Cottages and Pigeon House Road. All of these were a short walk from the quays where the boats would have been moored, now the East Link Toll Road. The Square in Irishtown can also be seen, where Dad’s family settled around the time Vivienne, the youngest in their family, was born. The Primary Care Centre is the old ‘Dispensary’, mentioned below.

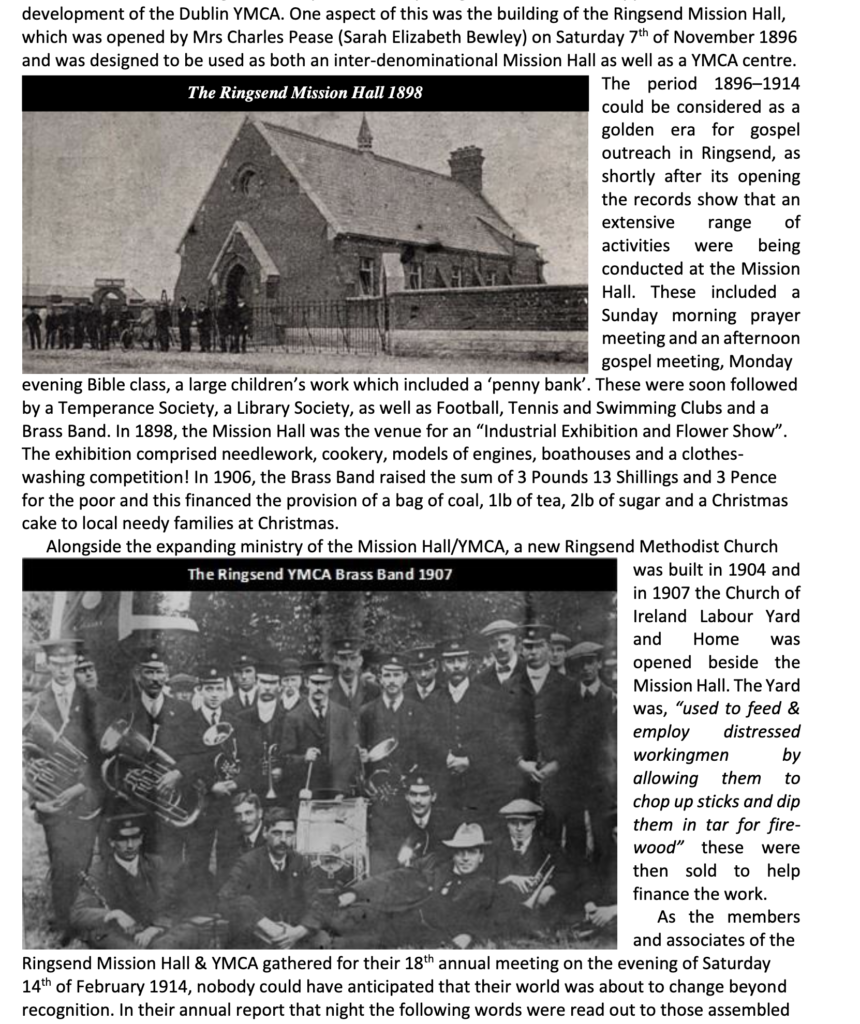

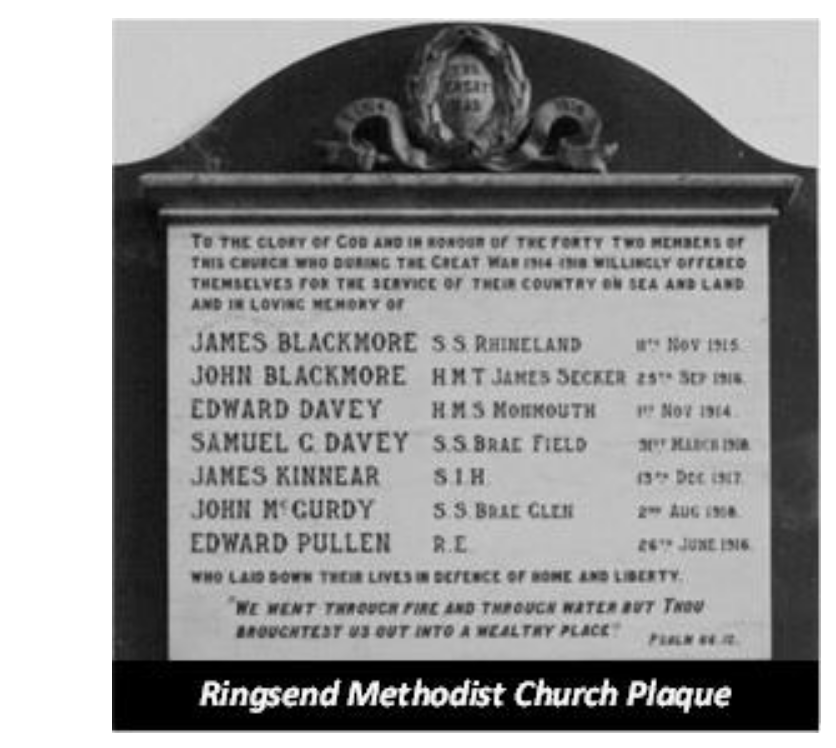

The native population of Ringsend would have been mainly Catholic before the Torbays arrived. There are clear patterns of intermarriage among the Devon families, unsurprising given their need to maintain a sense of community within the wider community but compounded by the requirement of the Catholic Church at the time to raise children of Protestant-Catholic marriages as Catholic. By 1911 almost one third of the population of the Pembroke township (containing Ringsend, Irishtown, Sandymount and Donnybrook) was non-Catholic. Religious observance was high in the Devon families and as Symes notes, and according to the ‘dundrummethodist’ post the Torbays carried on the Brixham tradition of always having a bible on board when going to sea. Their devotion to the scriptures is also seen in the use of biblical names, such as James, Abraham, Samuel, Rebecca, Rachel, Elizabeth etc., which persisted right through to the mid 1900s. The Torbays appear to have been central to the building of the Mission Hall and the founding of the YMCA in Ringsend in 1896, a philanthropic project of the Bewley family.

Families were large, as this was before the work of Marie Stopes. In the 19th century, modern contraceptive practices were not available to anyone, regardless of religious belief. Public health was at a very basic level. Infection control was minimal, housing conditions damp and unsanitary, and overcrowding the norm. When researching these families, it is horrifying to see how many children died young. For the poor and working classes, c. 1880, one third of deaths were infants under the age of 4. About 150 infants per thousand died in Dublin at this time. The Protestant community fared only slightly better than Catholic in Pembroke (14% vs 19% infant mortality), yet Ringsend fared worst in comparison to other parts of the township with an infant mortality rate of 20.9%.

Health services for the poor were confined to a small number of public hospitals, the Dispensary Doctor service and at worst, the Poor Law Unions system or the Asylum. There was no welfare state although the Dispensary Doctor system contained the seeds of what later became a national GP service and also the social welfare system. The Dispensary Doctor system involved getting a ticket from a local government official (if he thought the family were sufficiently destitute), to be taken to the GP to permit a free consultation. If a child was very sick, the ticket was red, giving rise the term ‘scarlet runner’. Interestingly, the building containing the social welfare office (now also primary care) in Irishtown when I was growing up was always referred to by Gran Hodgins as ‘the dispensary’. The coldly recorded figures in the census record of Susan Hodgins for 1911 brings the reality of the absence of a public health system, home, quite literally.

Workhouses and Asylums were the mainstay of the public health system. Workhouses were the result of the Poor Law system, present in England well before the 19th Century but only covering Ireland in 1838, under the Act for the Effectual Relief of the Destitute Poor. It was resisted by Irish politicians as being unsuitable for the Irish situation, yet was passed. People were only admitted to the workhouse when destitute and conditions were dreadful. The ‘work’ was menial and minimal, the food was scare and families were separated, often never to find each other again. The intention was that the conditions would act as a deterrent to entry.

For the poor the Union provided the only social security available. Without a public health system the workhouse hospitals were often the only health care that they had access to. Guardians also hired staff for the workhouses, teachers for the school and medical staff for the infirmary. They hired foster mothers and wet nurses for deserted children and, in later years, oversaw “outdoor” relief for those within the community. They also granted new clothing for inmates leaving the workhouse to go to work.

However many never left the workhouse and the stigma of it’s provisions cast a long shadow in Irish society for many years. It has been described as the most feared and hated institution ever established in Ireland. In 1850 there were c. 150,000 children in Irish Workhouses, although much less by 1900. Were members of the Memery, Gray or Hodgins families in the workhouse? The Find my Past site records the name Memery in the minute books in 1915, 1916 and 1917, including a William and a Brigid. There was one William Memery described as a Poor Law Guardian in the Irish Newspaper Archives, so this may the reason for his involvement although Brigid, who had 10 children, could not have been a Guardian, and must have been in receipt of poor law support. There are about 200 entries for the name Hodgins, although narrowing this to protestants in the South Dublin Union, there are only 5 (Robert, Richard, Rebecca, Henry and George) all between 1850 and 1862. This is the in the ‘Admission & Discharge’ Register, so it not known which the record refers to.

The 19th century was characterised by the exponential building programme for Lunatic asylums. Around the middle of the century 2-3 thousand people were housed in Asylums, the vast majority in appalling conditions, only barely better than farm animal accommodation. Between 1800 and 1900 at least 18 Asylums were built. By the 1902 there were 21,169 persons in Asylums and conditions had improved to a small degree. The vast majority were custodial institutions with virtually no provision of treatment. Although asylums probably housed people with the mental illnesses that we are familiar with today, the majority of inmates were committed for social reasons, for example pregnancy outside marriage, physical illness or old age, delinquency, poverty, or grief. Asylums also housed people with intellectual disability. We have no way of knowing how many of the extended family would have been committed to an Asylum but I think we can be sure, given the living conditions in Dublin and the breadth of the criteria for admission, some were. We can only hope they were discharged and did not die there, as it would most likely be a death experienced in squalor and misery.

During the first world war, Ireland was under British rule and many went to fight for the Allied Forces. Protestants were disproportionately represented in those who joined up and our ancestors were among that number. Five of Jem Memerys’ sons (one example below) were in the Navy and received WW 1 medals, as did three other Memerys.

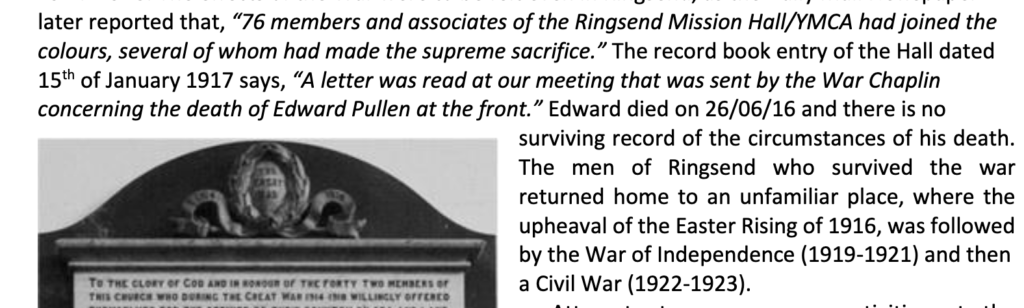

There may have been others, perhaps some of those I cannot trace, who lost their lives in the Great War. The War Memorials in Churches in Ringsend and Sandymount show that the Torbays were well represented among those serving ‘King and Country’.

It is not surprising that the Torbay families were more likely to have participated in the Great War than the Easter Rising, but we have very little information on any of this. There are no Memerys in the Irish Archive of Soldiers Wills, only one Hodgins (Drogheda) and only one Dublin-based William Gray. We don’t know if he was a member of the family, although the names and address suggest he could have been. The 1911 census shows a Kate Ryan at this address, but no Gray. William died in France in 1918, 4 months after he made this will.

Catholic canon law at the time insisted that all marriages involving Catholics should be before a Catholic priest and both parties had to commit to bringing up the children Catholic. It is hard to imagine today the huge difficulty this presented to our ancestors. While most married Protestants, there were several that did not. They faced potential exclusion and isolation from their family. Certainly one extended family member I met with, never met any of the Protestant side of his family until very late in life, a source of sorrow and disappointment to him. And of course, had Agnes not been persuaded not to marry Willie Galvin when they were younger, she might have had a very different life. I remember Dad talking about someone who having married a Catholic in a Protestant church, subsequently married (again) in the Catholic church, presumably to avoid disapprobation. Such marriages took place apparently ‘behind the altar’, that is not at the main altar, in a side altar or sacristy, and without the usual vestments, actions that clearly communicated disapproval of the ‘mighty Church’ and forced the couple to experience shame and a sense of inferiority. This practice persisted until the 1960s.

In general, the life of working class mothers in the 19th and early 20th century was particularly bad. They had no vote, little or no opportunity for education, had to care for children in poverty, and were only able to access health care if they had the money or if the child was near death’s door. I wonder did any support the Women’s Franchise League? It is interesting to see that the first woman (Constance Markievicz) to be elected to Government in 1921, stood in the Dublin South City constituency, which included Pembroke East where the Memerys and extended family lived. Only women over 30 with property could vote, so it is unlikely any of the family women had a vote. I sincerely hope at least one of men in the family gave her a vote. It is striking when looking through the newspaper archives for mentions of Memery or Hodgins, any records found are for men, with the sole exception of a Miss Memery who attended a commemoration for Lord Baden-Powell. The women are virtually invisible.

Neither state nor the dominant church appeared to be aware of the difficulties women faced at this time, seeing state funded medical systems to interfere with father’s rights to provide for the care of their children and seeing the destitute as the architects of their own misfortune. Protestant Church organisations were not much better. Gran Hodgins received help from the ‘Association for the Relief of Distressed Protestants (ARDP), founded in 1836 to ‘afford relief to necessitous members of any Protestant denomination (…) by means of grants of money, coal, provisions, tools, clothing and household necessities‘. This group although willing to give help, saw the requirement for it as due to moral failure on the part of those who needed it. This same assumption underpinned the labour project in Ringsend mentioned above. It cannot have been easy for her to seek help from this organisation (although I think we can safety say she would have scored well on the ‘exam’ below);

‘The thrust of the application form the ARDP used to assess the requests for assistance was not to determine the level of distress, or the relief it warranted, but rather to determine the moral worthiness of the applicant.

How long is the applicant known to the recommender?

Does applicant regularly attend divine service?

Are the children sent regularly to weekday and Sunday school?

Is applicant a member of any Scripture class Temperance or Benefit Society?

Is applicant in the habit of daily family prayer and reading the Holy Scripture?

Is applicant of clearly sober and industrious habit?

Matters did not improve much after the Foundation of the State, even with the public health bill in the 1940s that articulated a ‘Mother and Child Scheme’ which, if implemented would have provided free health care to all mothers and children up to the age of 16. The scheme was famously described as a scheme that ‘no one could object to with a name like that’, and equally famously countered with the observation ‘they could and they did’. Promoted but crucified by Dr Noel Browne, the scheme withered and all but died and the women in these communities that so clearly needed it were never to benefit from it’s intended provisions. My recollection of Gran Hodgins was that she was not a politicised woman, but I do recall my father saying that Gran attended the public speeches of Noel Browne, and, on researching the context of the lives of the woman in Ringsend in the last century, I understand better why she made this exception.

Belfast

The Hodgins familiy were from Lisburn, just outside Belfast and my ancestors on my Mother’s side were also from Belfast, and prior to that, Donegal. My Great Grandfather was born in 1867 in Donegal. He married there in 1897 and moved to Belfast soon after. He worked as a foreman in a brick yard.

In 1901 the population of Belfast was c. 350,000. Belfast was rapidly growing and on the way to becoming the most industrialised city in Ireland. The picture below is of City hall in 1902. It’s principal industries were linen making and shipbuilding. Belfast was the largest linen producing industry in the world. Many women were in employed in the Linen mills, and based on what I can find out about the Hodgins and the Walkers, this included our descendants. According to the Irish Archives…

Capital investment in technology, notably in mechanised spinning wheels, saw Belfast become the leading centre of linen production in the world. The linen mills were based mainly on the Antrim side, where they helped stimulate the development of other industries such as chemical manufacture. By the start of the twentieth century, more than 35,000 people worked in textiles in Belfast.

The iconic Belfast industry, however, was shipbuilding. It did not employ as many workers as the linen industry, but its achievements brought international renown to the city. Throughout the nineteenth century the shallow waters of the city were redeveloped into a major port, which were home to what became the largest ship-builders in the world. In 1859 Edward Harland bought the shipyard in the port which he had previously managed. Two years later he took Gustav Wolff as his partner. They expanded over the following decades, and by 1900 Harland and Wolff employed 9,000 people. In 1911 they launched the Titanic, then the largest ship in the world, which sank so dramatically on its maiden voyage.

My grandfather on my mother’s side, William Millington, came to Belfast to seek work, no doubt aware of the rapid expansion and the opportunities for employment. Her worked for some time in Harland and Wolff shipyard. The Hodgins family may have been involved in the linen industry. As outlined in the Irish Archives, despite its prosperity, there was poverty in the working classes. The poverty was not a rife as in Dublin, but significant. Many came in from rural areas to secure work including work for children to create sufficient income for the family to eke out a living. Over 2,000 children worked in some form or another by the turn of the 20th Century in Belfast. As with Dublin, the poor relied on the wealthy in local government to provide support for those in need, but were at mercy of attitudes which conflated poverty and idleness. The Poor Law system was in place here also, with workhouses in the city. A record for a Robert Hodgins who may or may not be my great great grandfather (see Hodgins Chapter) had a child, Selina, who was born and died in 1864 in the workhouse.

While industry provided work, conditions were dreadful. Mill workers were at risk for cotton lung and other respiratory complaints, while a host of risks attended those in shipyards or brickyards, such as falls, crush injuries and deafness. During the 19th Century, Belfast suffered a cholera epidemics, not doubt exacerbated by the crowed unsanitary conditions in the city slums. Those who worked in the mills were chiefly unskilled tradespeople, although there were skilled workers such as carpenters, sawyers and welders.

While Belfast did not have an aristocracy to rival British cities, there were clear social divides, with the wealthy captains of industry being principally Protestant. These families maintained control through their position in city commerce and also social structures such as the Orange Order and the Masonic Lodges. Sectarian tensions, a constant presence, were underpinned by economic factors – fear on the part of protestants of losing or having to share the proceeds of their prosperity. My ancestors in Belfast lived throughout the unrest at the prospect of Home Rule in 1909, the rising in 1916 in Dublin followed by independence and partition in 1922. What part they played in this is unknown.

2 responses to “Introduction”

Hello Margaret,

I am a Hodgins from USA. My father, Charles Hodgins, was sent at age 14 by his mother to live with an aunt, Emily Guest Hodgins (widow of Charles Hodgins, policeman) in Bronx, NY. The family were farmers in Co. Offaly and COI, however, I am finding farther back, they identified as Presbyterian and Methodist.

Hi Pamela Only noticed yr post now.

I am unsure if we are connected to Hodgins family in Offaly. I can trace my family back to a Robert Hodgins in Lisburn, Co Antrim c. 1820/30 but cant get any further as I have no other information. There are a lot of Hodgins families the midlands here and I have never known if our branch orginated there or not.